Yang Liping’s Rite of Spring | Peacock Contemporary Dance Company

One of the most intriguing things about Yang Liping’s Rite of Spring is its programmatic context.

Programmed as part of Brisbane Festival’s 2019 programme, the work sees landmark international choreographer Yang Liping and her ensemble (Peacock Contemporary Dance Company) create a new work around Igor Stravinsky’s revolutionary composition Rite of Spring.

Weirdly, this exact scenario played out almost exactly six years ago.

Programmed as part of Brisbane Festival’s 2013 programme, Rite of Spring saw landmark international choreographer Michael Keegan-Dolan and his ensemble (Fabulous Beast Dance Theatre) create a new work around Igor Stravinsky’s revolutionary composition Rite of Spring.

Stranger still, both works were programmed by different Brisbane Festival artistic directors – Noel Staunton in 2013, David Berthold in 2019.

Does this have a bearing on the quality or experience of Yang Liping’s Rite of Spring?

Not necessarily.

But, it does create an interesting context for engaging with the work.

What’s immediately obvious from the strange programmatic echoing of Rite of Spring is that people really like Rite of Spring. Or, by my reckoning, people are particularly drawn to the mythology surrounding Rite of Spring. After all, we’re not seeing recurring symphonic or musical renditions of Rite of Spring. We’re seeing recurring dance theatre versions.

People like the theatre of Rite of Spring.

If you’re not familiar, the story goes that, when Stravinsky unveiled The Rite of Spring in Paris in 1913 (where it was also accompanied with a dance performance), there was practically a riot. The crowds threw things at the orchestra for the entire duration of the performance. There was fighting, uproar, derisive laughter. It made headlines in New York, less than two weeks later. Again, in 1913.

There’s some debate as to just how violent this uproar was (one of the journalists who reported it later admitted he wasn’t actually there for the performance, for example) and who or what exactly had prompted the response. To some, it was the jarring minimalism of Stravinsky’s music. To others, it was the cacophonous stomping dance piece that accompanied it.

Regardless, the point remains – there was a hell of an impact.

To me, this creates a context through which to evaluate Yang Liping’s Rite of Spring. And, the fact that its Brisbane debut follows in the footsteps of a similarly premised production only makes that context more compelling. When looking at someone choreographing a new piece to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, you almost have to assess the results through the lens of:

What’s the impact?

Yang Liping’s interpretation of Rite of Spring, to that end, has a distinct advantage over Michael Keegan-Dolan’s. Perhaps due to a certain European fidelity or proximity to the 100th anniversary of the original production, Irishman Keegan-Dolan’s approach was indebted to aesthetics and images from early twentieth century Northern Europe.

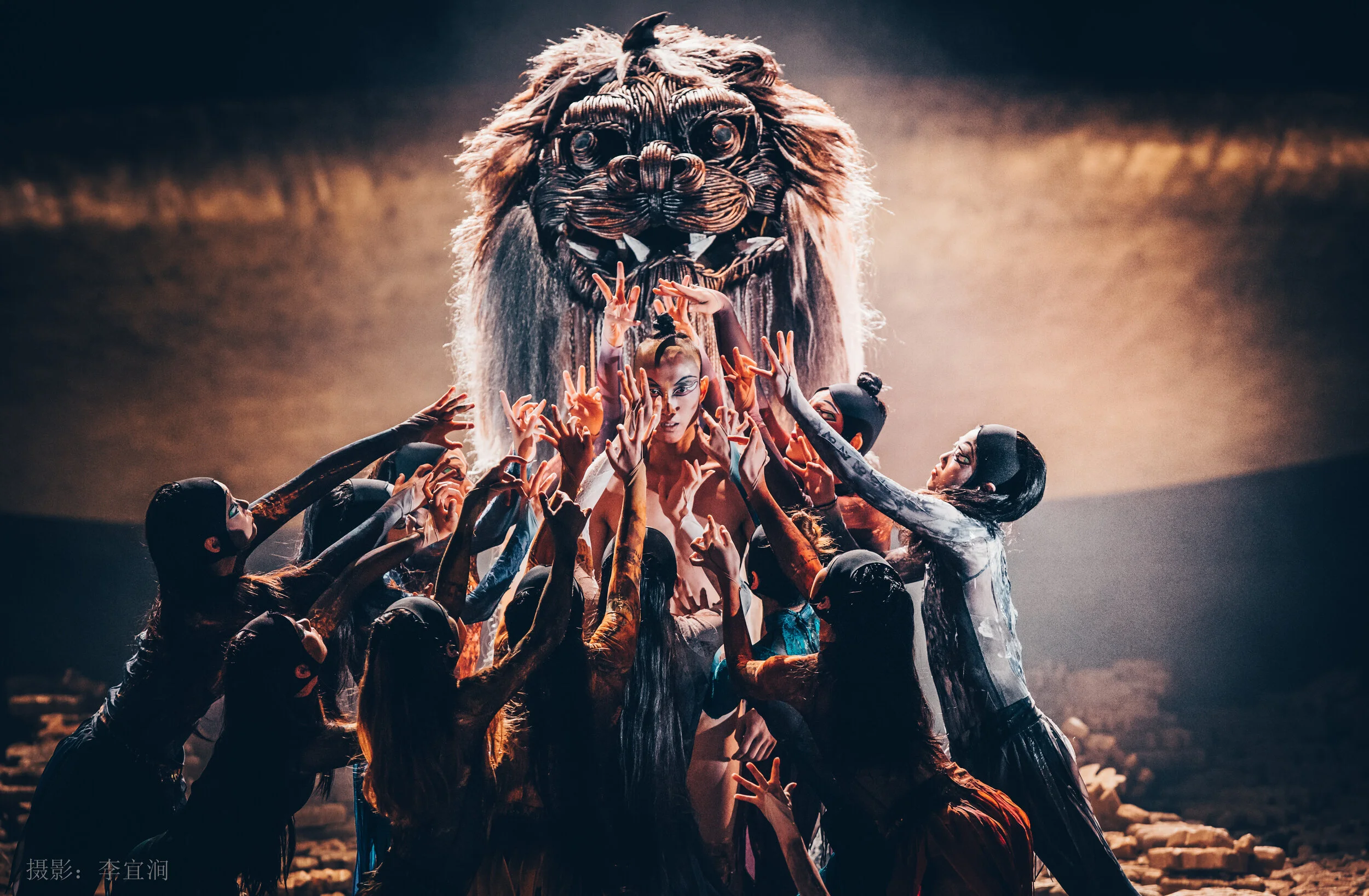

Liping, by contrast, shows no fidelity to Europe. She drenches her entire production in Chinese ideals and aesthetics. Upon entering the theatre and being greeted with a seemingly endless pile of golden Chinese symbols, strewn across the stage and being slowly gathered by a lone Buddhist monk, the audience knows they’re in for something truly different from previous incarnations.

And, truly, Liping holds nothing back. This Rite of Spring is sumptuous. It is gargantuan. At one point, the stage appears to be flooded with water as the dancers shimmer in darkness – fingertips glowing neon as their cascading movements approximate insects, flowers, and bird life. The set throughout is dominated by a huge metallic semi-circle – a gong, a rising sun, an apocalypse.

Surely, it’s one of the most illustrious and unpredictable experiences any audience-member will have in a theatre. It lurches from the patient, meditative opening to moments of almost pure anarchy. Golden light gives way to pure darkness. Dancers attack and exhaust themselves – euphoric and terrified. It’s a lot.

But, throughout, I kept returning to the ideas of Rite of Spring. That question.

What’s the impact?

Which might seem ridiculous, given what I’ve just described. The impact is immense, surely?

But, I’m not sure that the impact is that significant.

I’m not sure the impact is what it really should be, for a work premised around Rite of Spring.

Ironically, it’s the production’s best moments that really illustrated that for me.

What drove the madness in the audience in 1913?

While there’s debate as to the specific source (music or dance), the quality of the work that precipitated the riotous response seems to have more of a consensus.

Rite of Spring was raw.

The music was influenced by folk songs. The story was of a young girl being sacrificed for the good of the harvest. The choreography was atypically and overtly sexual. The subtitle of the work is ‘Pictures of Pagan Russia’. It ends with a girl dancing herself to death. The music was so famously and distinctly minimal that it’s argued John Williams nicked it for the two-note Jaws theme.

And, for the most part, Yang Liping’s Rite of Spring is not raw. It’s big, garish, colourful.

And, I know this – because, when Liping and her ensemble do go raw, it hurts.

I don’t mean it’s bad, either. I mean it hurts. It’s brutal, uncomfortable, transcendental.

The most powerful segment of the work, by a considerable margin, is a duet between a bestially costumed dancer and a woman sprawled on the floor. The physicality is strident. The stomach churns with both excitement and fear as it unfolds. It seems to last forever and yet is over entirely too soon. It echoes with the ache and exhilaration of sex.

It’s those moments where the work seems to lock into something greater. And, generally without exception, they’re moments where the artifice, scope and spectacle is actually stripped away. The heavy, ragged breathing as dancers devolve into repetitious anarchy. The solitude of a single dancer in motion. The rest of the work is very impressive. But, those moments have impact.

There’s an argument to be made that they have impact because the rest of the work is, by comparison, so elaborate – that it’s the contrast that creates the intensity. Similarly, there’s an argument to be made that such minimalism is simply something that particularly appeals to this reviewer. And, there’s weight to both those arguments.

But, again, I think of the context. I think of Rite of Spring.

And, to me, it’s only those moments that feel like they are truly suffused with the revolutionary legacy of Stravinsky’s composition. The rest of the work is daring, vast, beautiful, creative. There’s no real doubt that anyone who sees it will be left in awe. But, I don’t know if it actually succeeds in embodying or furthering the mythology of Rite of Spring.

Whether that matters is, of course, up to you.

For me, I think Yang Liping’s Rite of Spring would perhaps have been a much more powerful experience if it had hewed closer to the primal, stripped-back energy of its inspiration.

MJ O'Neill saw Rite of Spring on 25 September as a part of the 2019 Brisbane Festival. Rite of Spring played at QPAC until 28 September.

Director/Choreographer Yang | Li Ping

Composer | Igor Stravinsky and Xuntian He

Performers | Da Zhu (Fengwei Zhu), Xiaofan Feng, Maya Dong (Jilan Dong), Shui Yue (Han Xiao), Yimeng Li, Chengliang Lyu, Gloria Ng, Jinxia Ni, Ying Zhao, Ziye Chen, Yuqi Han, Qi Gao, Yuting Wang, Yue Yue, Chunyu Zhang