Lucie in the Sky | Australasian Dance Collective (ADC)

Complex technologies and their companion forms of artificial intelligence unsettle me. I confess upfront that I do not possess the language to articulate their overall exponential rates of development. Neither am I equipped with the faculties to fathom their boundless potential to radically impact humanity, the ecosystem of emotions we construct within ourselves, and the physical environments we inhabit in life-altering ways. Nevertheless, I am also deeply intrigued by the existence and evolution of these computing systems in equal measure.

All images: David Kelly

As Artistic Director of the Australasian Dance Collective (ADC) Amy Hollingsworth began her heartfelt welcome address to a resoundingly responsive audience and ended it on a note of visceral gratitude and nervous excitement, I watched the Playhouse at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre (QPAC) morph itself into a vessel poised to venture into and witness new frontiers of embodied and mechanised movements. ADC’s latest show Lucie in the Sky was to be a dynamic exploratory meeting between human corporeality and aviation technology in the form of microdrones.

Set against the riveting aural backdrop composed and designed by Wil Hughes, I could feel our collective presence sit on the wings of anticipation as the pulsating rhythms mimicked the sounds of a throbbing heart and reverberated around the theatre. We had become willing passengers and the proscenium stage a mysterious cockpit where bodies made of flesh and mechanical parts were ready to command our sensorial and intellectual capabilities.

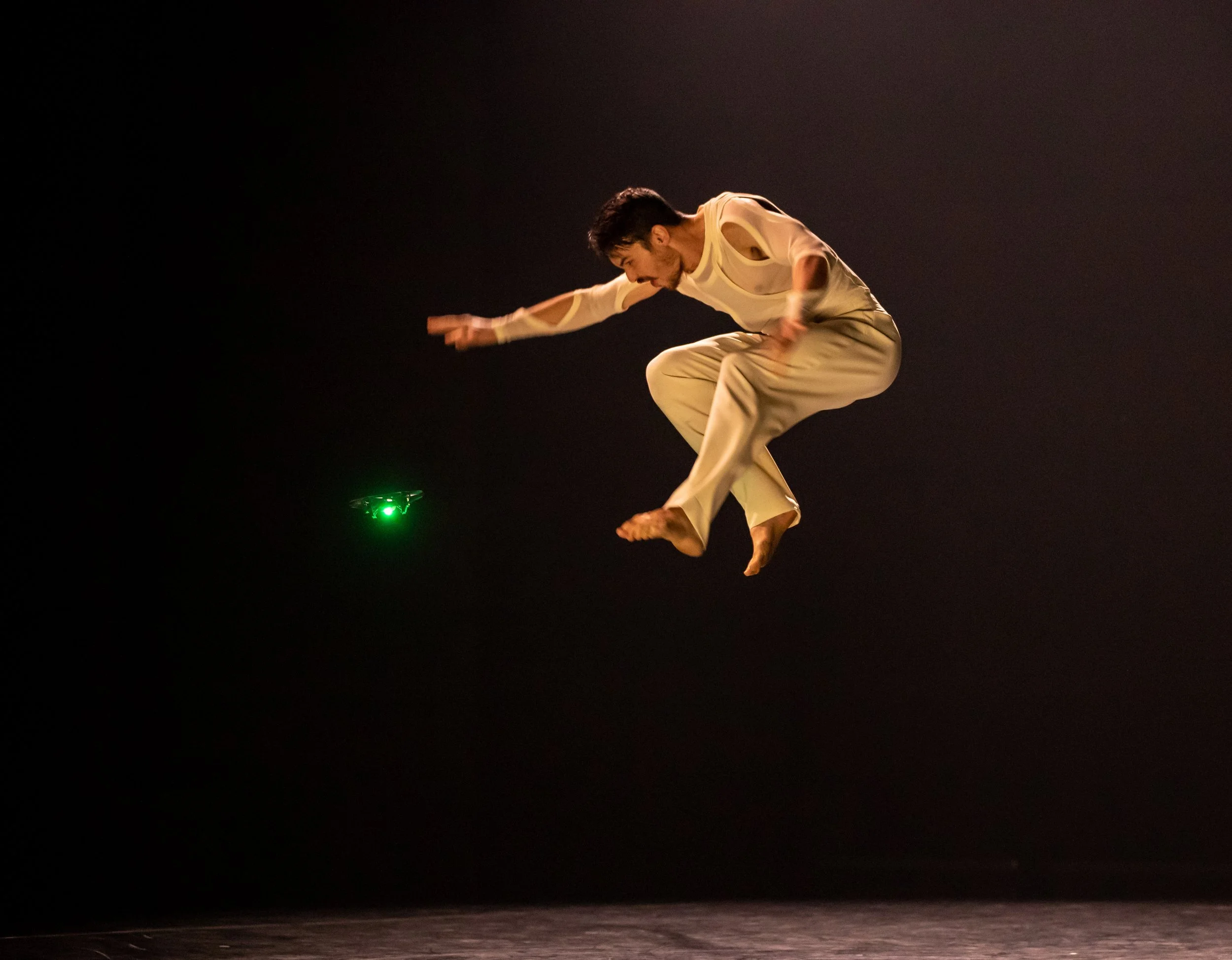

Lucie in the Sky, a brainchild of Hollingsworth’s, got off the ground in the most spellbinding of ways as company artist Harrison Elliot’s undulating form and lithe movements bewitched us. The lyricism in his moves were soon followed and matched by a swarm of circling microdrones. Although they buzzed around like bees humming in a state of ordered frenzy, they resembled starstwirling and twinkling in the night sky too. It was quite a sight to behold - mesmerising, really.

All images: David Kelly

There were, as a matter of fact, a series of moments of sheer choreographic genius, which evoked a range of emotions. The undeniable athleticism of the dancers and their propensity for imbibing the intensity of emotional and physical storytelling required of them resulted in a masterful rendering of their individual and collective choreographed sequences respectively. Dancers Taiga Kita-Leong and Jack Lister were a powerful duo whose display of leaps and moves aptly encapsulated feelings and ideas associated with freedom, flight, and levity. This coupled with costume designer Harriet Oxley’s clever sartorial creations served to further enhance the inherent choreographic capacity to hold richer, more layered conversations and inspire more meaningful connections between the dancers and their drone-friends.

Company artist Chimene Steele-Prior’s interaction with her microdrone highlighted just that. Select parts of her sleeves glowed a soft purple as she made deliberately miniscule gentle movements to introduce Lucie, a “shy, empathetic, loving drone”. In that moment and in that scene of surreal brilliance, the personality imbued upon Lucie seemed to come to life. A friendship predicated on quiet affection shone through in that instance.

In a similar vein, Elliot’s encounters with Skip, “an excitable, energetic drone” were particularly memorable as Skip became increasingly playful in his efforts to distract Elliot from dancing. The limber fluidity of Elliot’s physicality in his solo portion was interrupted by Skip’s desire to have fun with his friend. As Elliot gave in to Skip’s whims, both of them took turns to tease each other.

This light-heartedness in the choreography continued to persist, as the ensemble of dancers and drones reminded me of party-goers at a rave. A sliver of freeze-framed comic relief was delivered through a tableau that drew reference to the ape to man theory of evolution, except in this case the highest form of intelligence might now be artificial and far less human.

All images: David Kelly

The shift in mood from one of conviviality to one fraught with an increasing sense of foreboding began when dancer Lilly King was held captive by the blue light from the drone, possibly alluding to how addictive technological devices are and can be. With her gaze fixated on the drone, it was almost as if she had retreated from the real world. What remained was the deafening silence of isolation. These tensions rose when the other dancers took turns to crumble to the floor, embodying movements which seemed to cripple them in a sinister fashion. Company artist Chase Clegg-Robinson emoted and demonstrated with conviction a sense of disorientation so palpable it felt uncomfortable. A far from gentle reminder of the realities humanity has to grapple with in the face of fast-paced technological developments. The depths of despair and destruction technology can unleash cannot be ignored. The narrative that came to mind for me in this latter part of the performance was a cautionary tale of sorts, which disturbed me as much as it left me feeling a tad fatigued.

Lucie in the Sky is far more than a dance performance. It is an endearing and provocative work of art compelling us to consider either dipping our toes or perhaps even deep-diving into the fascinating world of cybernetics. A conversation-starter. A gentle provocation.

Additionally, as we continue to observe and evaluate the potentially detrimental repercussions of AI’s revolutionary progress on some businesses in our current technological climate, it begs the following question of primacy: What does it mean to see, situate, and elevate humanity at the centre, if not the forefront, of technology?

Experience Lucie In the Sky to be more than adequately inspired in your quest for answers.

‘Lucie in the Sky’ plays at QPAC until 13 May 2023.